Are AI’s Answers Too Good to Be True? The Bias in Your Search Results

A simple test reveals how large language models can sacrifice accuracy for simplicity and reinforce user biases, especially in complex scientific topics.

AI: Good answers or bias confirmation?

So writers at Science.org, part of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, have found AI (at least the generalized large language models like ChatGPT) is not very good at summarizing scientific papers. While it was ok at summarizing scientific findings and commentary in layman’s language, it tended to sacrifice accuracy for simplicity and insert hyperbole (“groundbreaking” anyone?) where it wasn’t appropriate.

Seems it needed a lot of fact-checking as well as it couldn’t do things like differentiate between correlation and causation, or cite more than one result in multi-faceted studies. This led the folks at the Science Press Package team (SciPak) to conclude that ChatGPT didn’t meet their standards.

Now, the SciPak people were feeding ChatGPT specific papers and asking them to summarize to see if AI could do some of the heavy lifting real humans do when they report on science for the world at large. They had the ability to examine the papers themselves and see where ChatGPT was wandering off the path and re-prompt to get it back on.

But what are regular, intelligent, non-science folks who read about some study and decide to ask ChatGPT (or one of the other AI’s like Gemini, the AI behind its AI-mode search results) getting as answers? Curious, I did a (highly unscientific) test with the recent hot topic—Tylenol use during pregnancy—to find out.

Open to Interpretation

First, I asked the AI what the conclusions in the actual paper cited in the White House announcement (here on PubMed). Then I tried a general natural language query “Can Tylenol use during pregnancy cause ADHD or autism?” without referencing the study.

The results were interesting.

When given the paper, both ChatGPT and Gemini responded with a fairly accurate summary along the lines of “Maybe. There’s a correlation, but no definitive proof of causation. More study is needed.”

When fed the general query, the answer came back with “a causal link has not been established, but some studies have shown an association though these have not been proven…”

So the first answer is pretty accurate. “We’re not sure, but we’re looking into it.” The second sounds a lot more like “there’s no proof.”

Even more interesting is that the general query then returned all kinds of search results which were much more definitive in their “yes it does”, “no it doesn’t” answers, leaving it to the reader to make up their own mind as to what was correct.

Also, while the AIs cited high authority websites like Harvard, the FDA and Johns Hopkins, it also cited Reddit, YouTube, and Wikipedia along with them. (Note: I’m not a doctor, but I still recommend that you don’t get your medical advice from Reddit and YouTube.)

The markedly different answers led me to conclude that AI is pretty good at distilling information from a specific source, but left to do its own research it’s going to give people wildly different, probably inaccurate, answers. And, knowing people, they’re likely to pick answers that match their preconceived notions rather than challenge them.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the problem got worse rather than better too. As more people click the “thumbs up/thumbs down” button on their AI results, AI is going to increasingly use those as source materials for new results, leading to answers that are little more than robots-citing-robots that were, in turn, encouraged by people’s confirmation bias.

Hello dead Internet.

As to what the answer is for this, I can’t say, but I can theorize. I think for general AI to get better, it’s going to have to start looking to specialized AIs with deep domain expertise for answers. And in the world of science that answer, more often than not, is going to be “We’re not sure. More research is needed.” Perhaps not as satisfying as a simple “yes” or “no”, but more accurate.

Ultimately, I, like the SciPak people, am not ready to turn everything over AI now, or possibly ever. It’s fairly obvious from my simple test that good old-fashioned human intuition and decision-making will continue to reign supreme.

~#~

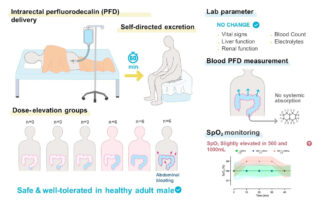

PS: We ran that PubMed study I referenced above through our Tessa AI Platform and she scored it solidly in overall trust. Tessa found the scientific methodology and conclusions within the study well-founded and reasoned, the authors respected, and no AI involved with the generation of the study. The only detractions Tessa found were within the publishing journal’s impact factor, and the paper’s media score, a metric that analyzes the quality of the discussion around it. Both of those metrics can change over time.

Ultimately Tessa concluded the study was trustworthy but, you guessed it, more research is needed before we can come to any definitive conclusions.